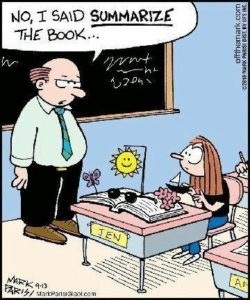

This week’s assignment for 6300 Understanding Writing as a Process course is to read and locate ourselves among the range of voices in “Bad Ideas About Assessing Writing” from the book Bad Ideas About Writing by Cheryl E. Ball and Drew M. Loewe. My reflection centers on two sections titled “When Responding to Student Writing, More Is Better” by Muriel Harris and “Student Writing Must Be Graded by the Teacher” by Christopher R. Friend. I was drawn to the section on responding because I’ve had my share of writing assessed by teachers who strongly favored that practice, and I wanted to explore whether my own perspective aligns with Harris’ position. The other section intrigued me because I wanted to discover Friend’s alternative approach to teachers grading papers.

Harris speaks to students being inundated with comments to the degree they lose focus. “Unfortunately, there is a point of diminishing returns when the comments become so extensive that students are overwhelmed, unable to sort out what is more important from what is less important (Ball and Loewe 268).” This was my experience when my writing was returned with the teacher’s red ink bleeding all over the page (high school English) or profuse comments in the margin (college English 1101).

I attempted to make all suggested changes and ended up writing what didn’t sound like me at all. I’d review the comments and try to picture my teacher or professor saying what I wanted to write. After revising my writing to mimic their voice, I would receive an excellent grade. I had never considered until now that I was literally writing for the teacher – not as in teacher being my audience, but as in teacher being the writer of my paper. Upon reflection, I dare say those teachers looked for their own images in the students’ writings rather than students’ representations of themselves. I agree with Harris’ statement: “The over-graded paper has little or no educational value (Ball and Loewe 269).”

Harris also factored students’ diverse literacy skills into the issue: “…that some students lack an adequate command of English because of inadequate literacy skills in general…Even students whose literacy level is adequate for college-level writing can be mystified by jargon that some teachers inadvertently use… (Ball and Loewe 270).” Although this was not my particular problem, I readily perceive how this may apply to students who aren’t fluent in the English language or those who are unfamiliar with pet terms some teachers favor.

Both Harris and Friend support the value of peer review as an alternative to over-grading. Not only does peer review exonerate professors from having students write for the teacher, the grading process is less labor intensive for professors who simply don’t have time to read and write responses for each paper in a class or multiple classes.

Harris puts forth teachers should recognize “…that not all writing needs to be graded. Taking pressure off not grading every single bit of composing allows writers to experiment, to ease the burden of a grade (Ball and Loewe 271).” According to Harris, students gain more from feedback in group peer review and reader response from tutors in writing centers, but students gain less from copious teacher comments.

Friend even refers to Harris’ section of the text with the suggestion extensive teacher commentary becomes meaningless to students. Friend poses a question and answer: “…wouldn’t it be better to help writers develop the ability to independently assess the quality of writing, either theirs or other people’s…If students learn to improve their understanding of writing by collaborating in groups that use writing to achieve a specific goal, then those groups should determine whether they met their own goal (Ball and Loewe 274-276).”

In search of outside sources on the subject, I came across an innovative approach by high school English teacher Melissa in her blog. This method calls for students to grade their own papers. I would have never considered it effective to have students grade themselves, but I find Melissa’s technique to be worth a try. I’m interested in what others think of her system.

I agree with Friend’s succinct conclusion of the matter. “If teachers stop grading student writing and instead focus on review and collaboration skills, each classroom would have a team of people qualified to assess the quality of writing. Teachers, then, could grade whether students provide beneficial peer review feedback and collaborate effectively – the meaningful work of writing (Ball and Loewe 277).”

Ball, Cheryl E., and Drew M. Loewe, Bad Ideas About Writing, West Virginia U, 2017. Web. 07 Oct. 2018. <https://textbooks.lib.wvu.edu/badideas/badideasaboutwriting-book.pdf>.

Image Courtesy of Pinterest

Hey Arlene,

You have some great insights on this topic. I really thought a lot about your view on how feedback from instructors can sometimes have a negative (or initially seen as negative) effect on the student’s voice in composition. I think that the solution comes down to (Kelley’s suggestion) a good approach to peer review and a special caliber of feedback for students to know how to write something in their own voice rather than write what they thing the instructor wants to read.

I really wonder how something like this can be accomplished. I think it’s probably a matter of more than a simple guide sheet. Like I said, revision from feedback on the peer-level can work nicely here because there is less of an authoritarian element to prompted revision tactics. If sessions are guided well, this could be all the student needs. But even still, peer review will always have its shortfalls. Sometimes students won’t have a good level of this needed consideration for one another in feedback (because they lack the voice necessary to consider how what they say will be interpreted? Perhaps).

From the standpoint of the instructor, I think it comes down to both a balance between highlighting on the student’s positives and negatives, and also providing feedback/marginal notes that the student can actually put to use because they emphasize ways to change what is being said while still guiding the student to maintain their voice.

Lot of good thinking here. Great post, Arlene.

Brian